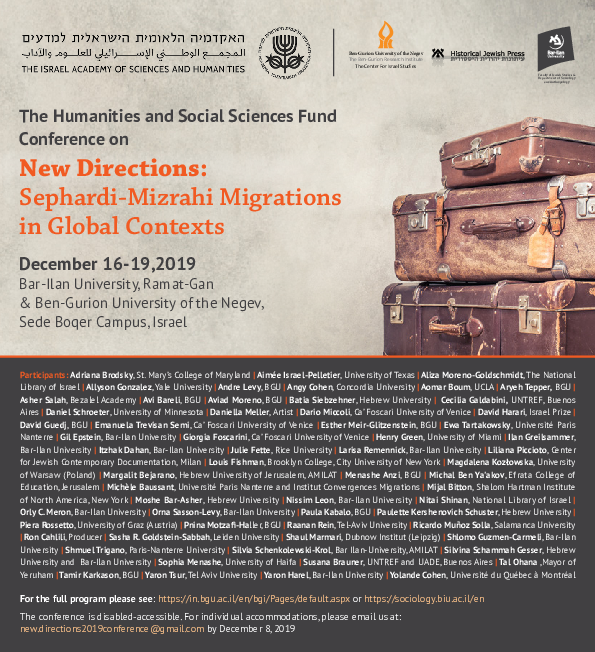

| In Honor of Mr. André Azoulay, Senior Advisor to Morocco’s King Mohammed VI, Founder of the recently inaugurated Bayt Dakira, and recipient of the ASF’s 2017 Pomegranate Award for Lifetime Achievement, for his latest honor, the Medallas de Oro de Andalucía (“Gold Medal of Andalusia”), presented in recognition of Mr. Azoulay’s “exemplary commitment to solidarity and harmony and for his pioneering approach at the head of the Foundation of Three Cultures, through which Morocco, Spain and Andalusia have been telling the world, for over twenty years, the art of living together.” Click here to dedicate a future issue in honor or memory of a loved one. 16 March 2020  Sephardi Ideas Monthly is a continuing series of essays and interviews from the rich, multi-dimensional world of Sephardi thought that is delivered to your inbox every month. The past two months of Sephardi Ideas Monthly (SIM) featured Dr. Aviad Moreno’s research into 19th-20th century migrations of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) Jews to various South American destinations. December’s SIM highlighted, “What Do You Know? Jewish Migration to Latin America,” Moreno’s piece on the global movement of Greater Sephardi Jews to Brazil and Argentina, while SIM’s January issue featured, “Globalizing the ‘Mizrahi Revival,’” an introduction to the Moroccan Jewish immigration to Venezuela. This month, SIM expands our vision and understanding of the past two-hundred years of MENA migrations with an original interview with Moreno. Focusing on the December 2019 conference that he initiated and organized in Israel, “New Directions: Sephardi-Mizrahi Migrations in Global Contexts,” Moreno clarifies why it’s so important to move beyond the conventional paradigms for viewing the migrations of MENA Jews, shares his personal connection to the topic, and explains the relevance of hosting the conference in Israel’s south, only a few meters from David Ben Gurion’s grave. SIM thanks Dr. Moreno for setting aside the time to share his ideas and research with our readers. |

Dr. Aviad Moreno, Ben Gurion University of the Negev (Photo courtesy of University of Pennsylvania’s Katz Center) Sephardi Ideas Monthly (SIM): What was the main idea behind the December conference, “New Directions: Sephardi-Mizrahi Migrations in Global Contexts?”Moreno: After the founding of Israel in 1948, the majority of Jews from Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) countries migrated to Israel, where they came to be known as Mizrahim. However, by the end of the 20th century, about a third of non-Ashkenazi Jews resided outside of Israel in countries such as Canada, France, Spain, Argentina, Italy, Venezuela, Australia, the US, and many other places. The conference provided a unique opportunity to host dozens of scholars from more than ten countries who shared their ideas and research about the local contexts—the various destinations—of Jewish migration from MENA countries. These cases are usually discussed separately from one another, so facilitating a conversation between these different local cases expands the ways in which we understand the history of MENA Jews after 1948. SIM: Do you have a personal connection to the topic? Moreno: Yes. I grew up in Beer-Sheva, which in the 1980s and early 1990s was a North African hub. In my school, seventy percent of the students were Moroccans and the rest were Tunisians, who didn’t get along with the Moroccans. We also had a few Ashkenazi Jews, who made an effort to become Moroccans! As the son of a father of Moroccan origin who had come to Israel from Venezuela and spoke Spanish as his native language, I was considered to be a very peculiar Moroccan, an “Ashkenazi-Moroccan” As I grew older, I became more aware of the public representation of Moroccan Jews and their migration history. I am referring here mainly to the idea that the diffusion of Zionism was limited to the so-called “traditional, lower class” strata of Jewish society, whose members made Aliyah as a consequence. On the other hand, according to that view, those who chose the “West” (France, Canada, Spain and the Americas, etc.), were part of the more “modernized” strata of local Jewish society and were indifferent to Zionism in general. That view did not align with my own family story: my late grandfather Alberto Moreno was a Zionist activist in Morocco and fluent in Hebrew. I have a letter in Hebrew that my grandfather sent in 1950 to the World Zionist Organization headquarters in Jerusalem, announcing an initiative to unify the Zionist bodies in Tangier, Morocco. The letter made it clear that he was the general secretary of the Tangier branch of the French Zionist Federation. Nevertheless, about three years later, my grandfather emigrated to Venezuela, but not before helping arrange the immigration of numerous Jewish teenagers from Morocco to Israel. My grandfather, a passionate Zionist activist, found himself in Venezuela and not in Israel. From there, he later sent my father to Israel on his own. That’s why I grew up in a family that is both Moroccan and Latin American. My family’s story is not necessarily unique, it resembles the stories of tens of thousands of families that originated in the Middle East and whose migration stories were more complex than the dominant narrative I was used to hearing in Israel about mass immigration from Arab countries. Some went from France to Israel, some left Israel for Canada. SIM: What was the advantage of holding the conference in Israel, particularly in a place like Sde Boqer? Moreno: Well, I think this global conversation about Jewish migration is especially relevant for the way we treat the immigration of Jews from Arab countries to Israel. Sde Boqer is situated in southern Israel, which is home to one of the largest demographic concentrations of Jews from Islamic countries in the world today. It is also a very symbolic place in terms of how we understand the motives for migrations. Sde Boqer is literally a few steps from Ben-Gurion’s grave, and his ambitious “evacuation” missions of Jews from Yemen, Iraq and Morocco during Israel’s early years were “the elephant in the room” throughout much of the conference.  SIM: Why was it important to discuss Ben Gurion’s legacy in a conference that dealt with global aspects of Sephardi migrations outside of Israel?Moreno: The idea that Jews needed to be evacuated was commonplace in Israel’s early years and was fueled by Ben Gurion’s perception of the Jewish Diaspora as divided into sections, largely defined by their location in the East or West. That conception led to the assumption that the state of Israel needs to “rescue” Jews from the hostile Middle Eastern environment, fulfilling the collective and deeply rooted Zionist ambitions of these populations. Now, this conception helps to describe the inner experience of some of the immigrants and some of those already in Israel, but it is far from comprehensive and, taken as such, it creates mental blinders. We should ask ourselves, for instance: why wasn’t the same conception applied to immigrants from the MENA region who chose to go to America? While this notion about MENA Jews being simply rescued has been heavily criticized by Israeli and non-Israeli scholarship, and also in a variety of popular discourses in Israel, we nevertheless continue to view this migration as a unique episode orchestrated by the state, and hardly related to the development of global Jewish and non-Jewish migrations over the last 200 years. The way we separate this migration to Israel from its larger global context of migrations is even reflected by the language we still use to describe that course of migration from the undeveloped world to Israel, he’alah (העלאה), a term that shares a linguistic root with Aliya and that practically can be translated to mean, “to transfer a passive population.” This conference helped to demonstrate that, regardless of Ben Gurion’s policy, Israel was in fact one major case within a wider migration decision-making matrix. We dwelled on voluntary and involuntary international migrations of Sephardi Jews that have been evolving since the 19th century, and that have continued to evolve throughout the world since 1948, when almost a third of MENA Jews migrated to destinations other than Israel. The conference’s speakers brought a wide-range of local perspectives on the different meanings of nationalism and ethnicity; east and west, Israel and diaspora. Perspectives that are evidently shaped by working on, and in, the different local centers of the Sephardi/Mizrahi diaspora today. SIM: Can you please give some examples? Moreno: We have historians who, for example, study Sephardi ethnicity in the contexts of Spanish nationalism and imperialism, Canadian bilingualism, Latin American colonial hierarchies, and Italian postcolonial migration. These histories are not necessarily confined to the pre- vs. post-1948 division so prominent in Israeli scholarship. In some of the presentations, migration begins already in the 19th century with early transregional ties beyond different regions. In others, it’s a very recent story of inter-national migration through America, Europe and Israel. From the perspective of this research, Israel is by no means the only Jewish center of the Sephardi Jewish diaspora, nor is there a well-defined country of origin, because Jews keep moving. Feature:  Dr. Aviad Moreno presented as part of a roundtable, “Reconsidering Moroccan Diaspora-Making” during the ASF Institute of Jewish Experience and Association Mimouna‘s “Uncommon Commonalities: Jews and Muslims of Morocco” Conference, Kovno Room, Center for Jewish History, 18 June 2019  The Monthly Sage החכם החודשי The Monthly Sage החכם החודשי Hakham Rachamim Hayuta HaCohen  Hakham Rachamim Hayuta HaCohen (Photo courtesy of HeHaCham HaYomi) The sage for the month of March, 2020, is Hakham Rachamim Hayuta HaCohen (1901-1959). Born and raised on Djerba, the center of Jewish scholarship in Tunisia, young Rachamim studied with Hakham Dido Hacohen, a “rabbi’s rabbi,” until, at the young age of fifteen, Rachamim studied with the great Hacham Kalfon HaCohen. After marrying, Rachamim—now Hakham Rachamim—served as the rabbinic court scribe until Hakham Raphael Mazuz, discerning a latent talent, asked him to begin teaching children. And Hakham Raphael Mazuz saw correctly: Hakham Rachamim proved not only to be a great scholar but a talented educator, encouraging his students (as well as his daughters) to record their Torah insights on a daily basis. Hakham Rachamim was offered the position of President of Djerba’s Rabbinic Courts in 1931 after the passing of the Gaon, Hakham Zion Hacohen Yehonatan, but he politely refused, preferring instead to teach. He finally accepted the position in 1950 upon the death of Hakham Kalfon HaCohen. In 1954, Hakham Rachamim immigrated to Israel and settled in Berachia, a moshav in southern Israel four kilometers east of the coastal town of Ashkelon. He was appointed the moshav’s rabbi upon arrival. In 1959, Hakham Rachamim passed away at the young age of 58, and was buried in Jerusalem’s Har HaMenuhot cemetery. Hacham Rachamim Hayuta HaCohen published many books, from studies of Jewish law to commentaries on the Bible, Talmud, and Passover Hagaddah. In the passage below, from Menachem Cohen, his commentary on the Torah, Hakham Rachamim emphasizes that the purpose of study is to act or to teach, not to engage in intellectual casuistry:Torah scholars who study only Talmud, and whose entire activity consists of pilpul (casuistry) and do not attend to also studying laws, are in error. For the purpose of studying Talmud is to learn the required laws, and to teach God’s laws. The purpose of study is to act or to teach, and one must allocate time to learning and considering the responsa of adjudicators, to know how to teach and how to act. One should set regular times for the study of Shulchan Aruch and its supplements to attain proficiency in knowing the laws, those that are currently applicable, in particular. For we see, to our chagrin, that some Torah scholars are extremely studious and precise, yet when confronted with questions of simple laws that are clarified in the Shulchan Aruch, even those laws of prayer and the recitation of blessings, do not know how to reply. They end up making secondary matters primary. For pilpul and cleverness were not created for their own sake, but to teach law. They serve to sharpen the mind so that it be prepared to learn rulings, questions and answers, and to teach God’s law and teachings, and to avoid errors when teaching. Continue reading… |