“When Sephardim were decolonized and dispossessed from Arab-majority lands that were their homelands for thousands of years, and now despairing about their peripheral existence in Ashkenazi-dominated Israel, they found a champion in the brilliant intellectual and moral voice of Albert Memmi”

~David Dangoor, President, American Sephardi Federation

Watch Rue Albert Memmi

Click here to dedicate a future issue in honor or memory of a loved one

The American Sephardi Federation’s Sephardi Ideas Monthly is a continuing series of essays and interviews from the rich, multi-dimensional world of Sephardi thought and culture that is delivered to your inbox every month.

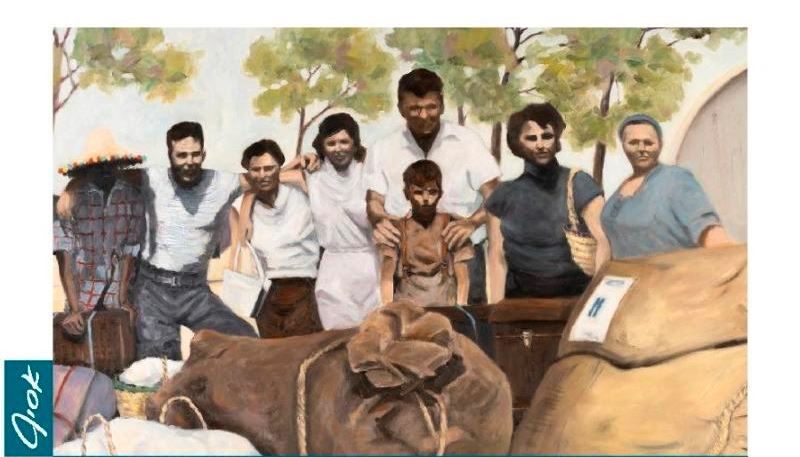

This month’s SIM shines the spotlight on a new path in Sephardi/Mizrahi historiography in an interview with Dr. Aviad Moreno from the Azrieli Center for Israel Studies at Ben Gurion University of the Negev. Dr. Moreno recently co-edited a Hebrew-language volume of essays, The Long History of the Mizrahim: New Directions in the Study of the Jews of Islamic Lands, that explores how Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews experienced their own lives and migrations to Israel, free from larger narratives. The approach might sound natural, perhaps even routine, but it’s relatively new to the scholarly scene, and it promises to deepen and expand our understanding of Greater Sephardi/Mizrahi history.

First, a little background. Sephardi/Mizrahi history is, like all of human life, absurdly rich in its variety, ranging across landscapes and, viewed from the inside, home to an often-bewildering diversity of perspectives, animated by internal but also cross-cultural social and spiritual connections, shaped by geo-political developments and moved by economic concerns, political pressures, and ancient dreams.

The historian stands before this embarrassment of riches in which “everything that has come down to us, in whatever form” functions as a source for writing history. The first step in gaining control over this mass of information is, as journalists say, finding an “angle” for telling the story, and this is where we encounter the main challenge affecting Sephardi/Mizrahi historiography: over the past seventy-five years, historians have been locked into two main angles when writing about the massive 20th century migrations of Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews.

First, because the majority of Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews made Aliya, or migrated, to the State of Israel, historians in the 1950s and 60s approached these events from the perspective of the modernizing, nation-building project of Zionism. From this perspective—this angle—the story to be told was how Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews were progressing from a traditional to a modern form of life, with “modern” understood in terms of secularized, contemporary European society.

This nationalist-modernist approach generated a reaction among historians who viewed Sephardi/Mizrahi history from a “separatist” perspective, decoupling Sephardi/Mizrahi Jewry from Jewish nationhood and viewing it instead from a post-colonial or neo-Marxist angle in which a single riff repeats itself in an endless loop, namely, how Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews were abused and oppressed by forces rooted in the West.

It’s possible to add additional “angles” that, in effect, silenced the voices of Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews themselves. Arab historians viewed Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews as collaborators in an oppressive European colonial project, and entire histories fell under the radar: what about Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews who migrated to the Americas? Or what happens to the stories of Sephardi/Mizrahi communities that migrated piecemeal to Israel and whose history continued as a kind of dialogue between Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews in Israel and their communal brethren still in the country of origin? In telling these stories, the historian who seeks to explore the power of human experience needs to move gracefully between different “centers,” and not to stake his or her flag in one place and view that perspective as sacred ground.

In response to these two dominant “schools”—secular-Zionist and post-colonial—some historians tried to identify what was useful in both while delineating a middle path that recognized the intensely powerful historical reality of Jewish national solidarity, while also acknowledging the ways in which Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews were, in many cases, viewed and treated with condescension, if not contempt.

This revision was indeed helpful, but it still missed what Dr. Moreno and his colleagues are trying to do: let the Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews speak for themselves, independent of larger historical framings.

Sephardi Ideas Monthly is delighted to share our interview with Dr. Aviad Moreno and, in so doing, to share with our readers the trailblazing, new perspective that is enriching our understanding of Sephardi/Mizrahi history and with it, Jewish history as a whole.

Sephardi Ideas Monthly: Dr. Moreno, please explain how, in your book, The Long History of the Mizrahim: New Directions in the Study of the Jews of Islamic Lands, you and your colleagues challenge some of the dominant perspectives in the field of Sephardi/Mizrahi Studies, particularly with regard to the way in which we tell the story of Sephardi/Mizrahi migrations in the 20th century.

Moreno: If we go back to Israel’s early years, the Jews collectively known as “Oriental Jewry” were viewed from the perspective of a large nation-building, modernizing project. Academic researchers examined edoth, Jewish ethnic groups that, it was assumed, would “progress” and shed their particular characteristics within the national Jewish melting pot. But, broadly speaking, the melting pot was designed to Europeanize everything. Now, despite some obvious differences, this analytical perspective was shared in other immigration-absorbing countries such as Australia and Brazil, where the national modernization projects also assumed European norms.

Beginning in the 1970s, however, academic discourse in the humanities and social sciences started to change. The nationalist framing of ethnic groups was challenged, and multiculturalism and hybrid identities were celebrated. There were a series of “turns,” such as the “cultural turn” followed by the “post-colonial turn,” and as a consequence, by the 1980s Jews from the Arab and Muslim world in Israel—now collectively known as Mizrahim—were being studied as another ethnic minority in post-national and post-colonial contexts and re-framed as underdogs within a global system of “Western hegemony” that included “white” or Ashkenazi Jews.

SIM: So it sounds like either way, the perspectives of the Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews themselves were overlooked, and their stories, as they experienced them, weren’t told.

Moreno: Yes, but we’re not there yet, there’s another layer.

Within this larger reaction against “Western hegemony,” non-Jewish historians of the Middle East and North Africa sought a voice of their own, with the added caveat that they often frame Muslims as underprivileged groups within the global system of Western hegemony. The analysis of Jews as minorities in Islamic societies is obscured by this framework, while post-colonial and nationalist narratives across the Arab world often portray Jews as collaborators in an oppressive European project. This explains the tendency in some nationalist historiographies from the region to frame Jewish migrations as processes of voluntary disengagement from the Islamic world that was facilitated by the foreign intervention of Zionism or colonialism. And as a consequence, Jewish migrations were never studied as part of the broader post-colonial movement of communities from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) to the West.

So this was state of the discipline until the turn of the millennium, and it left very little room for exploring more nuanced transregional connections and broader questions of migration and displacement.

But things are changing. Recent studies of the history of Jews across the MENA region have been questioning the orthodoxy of probing the 20th century fate of MENA Jews according to East/West or national/post-national binaries, or Ashkenazi/Mizrahi dichotomies. These studies are generating fresh perspectives on communal histories that are humanly richer and more complex than the rigid categorizations usually employed in interpreting them.

Here I should add a footnote. There’s an unavoidable semantic trap. Our book critiques generalizing terms like “Mizrahim,” at the same time that we use the term. We want to make distinctions and see with greater nuance, but generalizing terms like “Mizrahim” are “first for us,” they’re what’s used as currency in popular discourse, and they’re necessary for beginning to study, think and talk about the field. This is part of the reason why we chose to include “Mizrahim” and “Jews from Islamic Lands” in the title of our book, together with the different case studies in the book itself.

SIM: So please share a few case studies from the book.

Moreno: Sure. Remember, until recently we’ve been given a static picture of Jewish minorities caught between oppressive Islamic regimes, the schemes of Western powers and/or the designs of the largely Ashkenazi Jewish nation state. Whatever the case, it’s as if these are people without any agency. The cases appearing in our volume offer some much-needed nuance and make necessary distinctions.

For instance, you can’t explain Algerian Jewish migrations to France after 1962 as a repeat of Iraqi Jewish migrations in 1951 to Israel. Each migration is a world unto itself, but all-inclusive perspectives overlook sub-regional and local migration processes. You also need to consider how social ties and cultural background impacted the ways in which people responded to these large-scale events, as well as what connects earlier migrations to the mass movements after 1948. So, in our volume, you’ll find the stories of transnational Yemeni-Jewish networks beginning at the end of the 19th century that extended from the Red Sea coast all the way up to the Mediterranean port of Jaffa, or rabbinic lines of communication that extended from Gabes, Tunisia to Afula in post-’48 Israel. The dominant ways of writing Sephardi/Mizrahi history are hard-wired not to see these connections.

Another example is the book’s focus on intra- and inter-group power relations among communities of Jews from Islamic countries, across national, colonial, post-colonial and socio- linguistic contexts. Daniel Schroeter’s article is a helpful example. Instead of limiting himself to analyzing Moroccans vis-à-vis Ashkenazim in the Jewish state or Moroccan Jews under Islamic or colonial rule, he traces the ways in which Moroccan Jews have asserted their exceptional communal experience within MENA Jewish history, and then explores how this self-assertion has shifted from the Moroccan context to the Israel’s multiethnic environment.

But telling the story from “within” also means studying MENA Jews as multilayered societies that shaped their identities in constant interaction with the different groups they came into contact with, both within and beyond the “region.” The book challenges the assumption that the history of Mizrahim needs to be studied on its own. Jessica Marglin’s article is a pertinent example. She offers a valuable case study of the encounter between traditional and modern legal systems across the Mediterranean connecting Livorno and Tunisia. Her conceptual framing – and the sources that she utilized – enrich the historical study of European and North Africa Jews with a cross-cultural and transregional perspective.

These are just a few of the many complexities that the book highlights while attempting to capture the recent diversification of research trends. These historical studies defy the rigid categorizations that were once so prominent in the analyses of Jews from Muslim countries and, as a consequence, deepen our understanding of the complex and rich character of Sephardi/Mizrahi life and experience.

SIM: Thank you

~~~~~~~

In honor of 30 November, the ASF’s Institute of Jewish Experience organized a first-of-its-kind global event, “Reclaiming Identity: Jews of Arab Lands and Iran Share Stories of Identity, Struggle, and Redemption,” which is continuing now as a podcast series celebrating our peoples’ struggles and triumphs.

~~~~~~~

The American Sephardi Federation invites all individuals, communities, and organizations who share our vision & principles to join us in signing the American Sephardi Leadership Statement!

Please also support the ASF with a generous, tax-deductible contribution so we can continue to cultivate and advocate, preserve and promote, as well as educate and empower!

Make checks payable to “American Sephardi Federation” @ 15 West 16th Street, New York, NY, 10011.

Email us at info@americansephardi.org if you are interested in discussing donating securities or planned giving options with a financial professional from AllianceBernstein.

~~~~~~~

The Monthly Sage החכם החודשי

This month’s featured sage is Hakham Shlomo Katzin (1909-1982).

Shlomo Katzin was born in Jerusalem to Hakham Shaul Katzin, a noted kabbalist who served as Shlomo’s first teacher. Young Shlomo later studied at the celebrated Porat Yosef Yeshiva in Jerusalem, where he learned under R’ Ezra Atia and R’ Ya’akov Adas.

Hakham Shlomo Katzin was ordained to the rabbinate by the Rishon LeZion and first Sephardi Chief Rabbi of the State of Israel, Hakham Ben Zion Meir Chai Uziel, of blessed memory. Hakham Shlomo then served as rabbi of the Nachalat Achim and Nachalat Zion Jerusalem neighborhoods, until he was asked by the heads of the Egyptian Jewish community to lead the Egyptian rabbinic court. He accepted. In addition to his rabbinic studies, Hakham Shlomo Katzin was a popular preacher, a qualified ritual slaughterer and served as a mohel.

In 1948, Hakham Shlomo returned to the independent State of Israel, and served as rabbi and judge in Jaffa, where he founded the Shivat Zion synagogue. Hakham Shlomo then moved to Bnei Brak, where he served as a judge in the Tel Aviv rabbinic court.

Hakham Shlomo Katzin passed away on the 6th of Heshvan, 5743 (1982). He is the author of Kerem Shlomo, a collection of novel Talmudic interpretations, halakhic responsa, and popular sermons; Divrei Shlomo, a collection of halakhic responsa and sermons; Taharat Bnot Israel, rulings regarding family purity and ritual baths; and Nitzotzei Or, a work centering on ethics and character development.

In the following passage from Nitzotzei Or, Hakham Shlomo elaborates on scholars’ moral and religious obligation to cite their literary sources:

I find it appropriate to remind and warn all authors of their obligation to explicitly cite their sources, and to not appropriate the respect that is due to Torah scholars. Others before me have gone to great lengths in denigrating those who neglect crediting their sources, and go about furtively speaking of ideas and conceptions as though they conceived of them themselves. On this matter, the author of Sha’ar Asher, of blessed memory, wrote that one who so acts robs both the living and the deceased. Such a person robs the living because he could have brought about the Redemption, since it says, ‘Whoever declares something in the name of its originator brings Redemption to the world’; such a person robs the deceased as well, for mentioning their names makes their lips stir in their grave… These two sayings should suffice for anyone whose heart has been touched by the awe of God. There is, in addition to the obligation to cite one’s sources that we mentioned, great privilege to be gained, for this results in positive regard and a good recommendation [for the World-to-Come] because the pleasure it causes above stirs the compassion of Heaven.

~~~~~~~

The Wolf of Baghdad (Memoir of a lost homeland)

By Carol Isaacs

In the 1940s a third of Baghdad’s population was Jewish. Within a decade nearly all 150,000 had been expelled, killed or had escaped. This graphic memoir of a lost homeland is a wordless narrative by an author homesick for a home she has never visited.

Transported by the power of music to her ancestral home in the old Jewish quarter of Baghdad, the author encounters its ghost-like inhabitants who are revealed as long-gone family members. As she explores the city, journeying through their memories and her imagination, she at first sees successful integration, and cultural and social cohesion. Then the mood turns darker with the fading of this ancient community’s fortunes.

This beautiful wordless narrative is illuminated by the words and portraits of her family, a brief history of Baghdadi Jews and of the making of this work. Says Isaacs: ‘The Finns have a word, kaukokaipuu, which means a feeling of homesickness for a place you’ve never been to. I’ve been living in two places all my life; the England I was born in, and the lost world of my Iraqi-Jewish family’s roots.’

Maimonides, Spinoza and Us: Toward an Intellectually Vibrant Judaism

By Rabbi Dr. Marc D. Angel

A challenging look at two great Jewish philosophers, and what their thinking means to our understanding of God, truth, revelation and reason. RAMBAM/Maimonides is Jewish history’s greatest exponent of a rational, philosophically sound Judaism. He strove to reconcile the teachings of the Bible and rabbinic tradition with the principles of Aristotelian philosophy, arguing that religion and philosophy ultimately must arrive at the same truth. Baruch Spinoza is Jewish history’s most illustrious “heretic.” He believed that truth could be attained through reason alone, and that philosophy and religion were separate domains that could not be reconciled. His critique of the Bible and its teachings caused an intellectual and spiritual upheaval whose effects are still felt today.

R’Angel discusses major themes in the writings of Maimonides and Spinoza to show us how modern people can deal with religion in an intellectually honest and meaningful way. From Maimonides, we gain insight on how to harmonize traditional religious belief with the dictates of reason. From Spinoza, we gain insight into the intellectual challenges which must be met by modern believers.

~~~~~~~

The ASF Institute of Jewish Experience presents:

Torah and “Secular” Studies in the writings of Hakham Yosef Qafih (1917-2000)

(3 Part Series)

Join us for Part 1 with David Hazan: “Insights from our hakhamim by students of The Habura”.

Thursday, 3 March at 12:00PM EST

(Ticket: $5 per session)

Sign-up Now!

Sponsorship opportunities available:

info@americansephardi.org

===

The ASF Institute of Jewish Experience presents:

Paving a New-Old Path: The Integration of Jewish Yemenite Folk Music in Israeli Art Music

The immigration of the Jews of Yemen to Israel began in the 13th century and lasts until this day. With them, Yemenite Jews brought their unique culture as reflected in their clothes, jewelry, food, art, dance and music.

The presentation deals with the meeting of five Israeli composers from the first generation who were educated in the western music style, combining the folk Yemenite music that the immigrants brought with them. In analyzing the Jewish Yemenite folk music as well as music compositions influenced by these folk songs, the level of influence was checked in matters of folk vocal sound production, texture, typical intervals, modes and maqamat and other folk-Yemenite parameters.

This research examines the ways any of those parameters appear in the concert music in pure, altered or complex way.

Sunday, 6 March at 12:00PM EST

(Ticket: $10 per session)

Sign-up Now!

About the speaker:

Naama Perel-Tzadok completed her MA studies in Music Composition at Haifa University, Israel. She has written music for diverse ensembles, and today they are performed by different orchestras, ensembles and choirs in Israel.

These days, she’s a lecturer at the technological college “Kineret”, in the sound engineering department.

Sponsorship opportunities available:

info@americansephardi.org

===

The ASF Institute of Jewish Experience presents:

Iranian Jewry: A Brief History

Dr. Daniel Tsadik Shares History

Jews have lived in Iran for more than 2,000 years. This ancient community had its trials and tribulations, but remained until today. Despite all vicissitudes, Iranian Jews remained true to their roots and connected to their heritage for generations. Dr. Daniel Tsadik will provide an overview of the Jews in that region from ancient times until today.

Tuesday, 8 March at 12:00PM EST

(Ticket: $10 per session)

Sign-up Now!

About the speaker:

A Fulbright scholar, Dr. Daniel Tsadik obtained his PhD in 2002 from the Yale University History Department. He authored several articles, a book entitled Between Foreigners and Shi‘is: Nineteenth-Century Iran and its Jewish Minority (Stanford University Press, 2007), another book entitled The Jews of Iran and Rabbinic Literature: New Perspectives (2019), which won the Israel Prime Minister Prize, and co-edited the book Iran, Israel and the Jews: Symbiosis and Conflict from the Archaemenids to the Islamic Republic (2019). From 2008 to 2020, Professor Tsadik taught at Yeshiva University, where he served as Associate Professor of Sephardic and Iranian Studies. His current research is on Shi‘ite-Jewish polemics.

Sponsorship opportunities available:

info@americansephardi.org

===

The Department of Anthropology & Archeology at the University of Calgary, Schusterman Center for Israel Studies, Brandeis University and Belzberg Program in Israel Studies, University of Calgary, & the American Sephardi Federation present:

Sephardi Thought and Modernity 2022 Webinar Series

Continuity and Rupture in Sephardi Modernities

(Second Edition)

On Wednesdays at 1:00PM EST

(10am Pacific / 1pm Eastern / 6pm UK / 8pm Israel / 9:30pm Iran)

(Complimentary RSVP)

9 March

Deborah Starr (Cornell University) and Eyal Sagui Bizawe (Hebrew University of Jerusalem) Nostalgia as Critique: The Case of Jews in Egyptian Cinema

13 April

(10am Pacific / 1pm Eastern / 5pm UK / 7pm Israel / 8:30pm Iran – note time – US Daylight Savings)

Julia Philips Cohen (Vanderbilt University) and Devi Mays (University of Michigan) Middle Eastern and North African Jews in Paris: A Forgotten Chapter

11 May

(10am Pacific / 1pm Eastern / 5pm UK / 7pm Israel / 8:30pm Iran – note time – US Daylight Savings)

Vanessa Paloma Elbaz (University of Cambridge) Rhizomic networks of unruptured continuity from 16th c. Italy to 21st c. Casablanca: Music, Power, Mysticism and Neo-Platonism

In this second edition of the Sephardi Thought and Modernity Series we will focus on the question of continuity and rupture as a way to deepen our dialogue about the different forms that modernity has adopted throughout Sephardi history. We will discuss questions such as the meaning of the concept of “modernity” in non-European contexts such as the Levant and/or the Arab world. We will explore how non-European Jewish societies developed ways of life and practices that synthesized tradition, change and cultural diversity throughout time. We will delve into Sephardi intellectual life, cosmopolitanism, cultural belongings, language, translation and mobility.

===

The ASF Institute of Jewish Experience presents:

Sepharadi approach to Talmud Torah in the writings of Hakham Yosef Faur (1934-2020)

(3 Part Series)

Join us for Part 2 in our series “Insights from our Hakhamim with the students of The Habura.”

Thursday, 10 March at 12:00PM EST

(Ticket: $5 per session)

Sign-up Now!

About the speaker:

Yonatan Rahmani is a Jewish educator living in NYC. After completing the Springboard Fellowship at CUNY Queens College Hillel, he moved to Jerusalem to study at the Pardes Center for Jewish Educators. Yonatan returned to NYC as a member of the NYU Bronfman Center’s Student Life team, before joining YCT as a member of the inaugural JEWEL program. Yonatan is happiest when cooking, learning, hosting guests for Shabbat, and spending time with his family.

Sponsorship opportunities available:

info@americansephardi.org

===

HUC-JIR Jewish Language Project, Iranian American Jewish Federation, Nessah Synagoque, and USC Caden Institute present:

Languages of the Jews of Iran: A series of online conversations and performances

On Sundays at 1:00PM EST

(10am Pacific / 1pm Eastern / 6pm UK / 8pm Israel / 9:30pm Iran)

(Complimentary RSVP)

13 March

(10am Pacific / 1pm Eastern / 5pm UK / 7pm Israel / 8:30pm Iran – note time – US Daylight Savings)

Judeo-Persian in the 20th century: New research

Dr. Habib Borjian and Ibrāhīm Šafiʿī present personal documents written in Persian in Hebrew letters, and Alan Niku discusses the distinctive Tehran Jewish dialect of Persian based on recordings and fieldwork. Then, Cantor Jacqueline Rafii presents Passover psalms translated into Judeo-Persian and recorded by her grandfather in Tehran in 1971.

Jews in Iran historically spoke many languages – from Semitic, Median, and Persian language families. The languages/dialects of Jews in different cities and towns were so different that their speakers often could not understand each other. Now these longstanding Jewish languages are endangered, as most Jews shifted to standard Persian in Iran or to Modern Hebrew, English, and other languages after emigrating.

The HUC-JIR Jewish Language Project presents a series of conversations and performances highlighting this rich linguistic heritage. By attending these events, you will learn how Jewish languages compare to each other and to local Muslim, Zoroastrian, and Christian languages. You will be inspired by the elderly speakers and young activists who are working hard to preserve them for future generations. And you will be entertained by new songs in Judeo-Isfahani, Judeo-Hamadani, and Jewish Neo-Aramaic.

These events will last for 75 minutes. Please register for each event separately. While the Jewish Language Project usually posts recordings of events the following day, these events will only be accessible at the times they are presented (due to security concerns and preferences of some of the presenters). These events will also be screened in person at Nessah Synagogue in Beverly Hills, California. Learn more and RSVP for the in-person screenings here.

===

The ASF Institute of Jewish Experience presents:

Kavkazi, Georgian, and Bukharian Jews: At the Crossroads of Sephardic, Mizrahi, and Russian-Speaking Worlds

(3 Part Learning Series)

The histories and cultures of Bukharian, Kavkazi (Mountain), and Georgian Jews are situated at the unique intersection of Sephardic, Mizrahi, and Russian-Speaking Jewish (RSJ) identities. Through this 3-part learning series, we will explore the multilayered and rich stories of these millennia-old communities in Central Asia and the Caucasus—discovering the ways in which they have developed their mosaic cultures through dynamic interactions with the dominant and changing societies surrounding them. Our discussion will also shed light on how their experiences fit into the broader historical saga of the Jewish people.

On Tuesdays at 12:00PM EST

(Ticket: $10 per session)

22 March

(Part 3)

Sign-up Now!

About the Speaker:

Ruben Shimonov is an educator, community builder, and social entrepreneur with a passion for Jewish diversity. He previously served as Director of Community Engagement and Education at Queens College Hillel. Currently, Ruben is the American Sephardi Federation’s National Director of Sephardi House and Young Leadership. He is also the Founding Executive Director of the Sephardic Mizrahi Q Network and Director of Educational Experiences & Programming for the Muslim-Jewish Solidarity Committee. He is an alumnus of the COJECO Blueprint, Nahum Goldmann and ASF Broome & Allen Fellowships for his work in Jewish social innovation and Sephardic scholarship. He has been listed among The Jewish Week’s “36 Under 36” Jewish community leaders and changemakers. Currently, he is a Jewish Pedagogies Research Fellow at M² | The Institute of Experiential Jewish Education. Ruben has lectured extensively on the histories and cultures of various Sephardic and Mizrahi communities. He is also a visual artist specializing in multilingual calligraphy that interweaves Arabic, Hebrew, and Persian.

Sponsorship opportunities available:

info@americansephardi.org

===

The ASF Institute of Jewish Experience presents:

New Works Wednesday with Lior Sternfeld

Join us for New Works Wednesdays with Associate Professor Lior Sternfeld as he discusses his book Between Iran and Zion: Jewish Histories of Twentieth-Century Iran

Wednesday, 23 March at 11:00AM EST

(Complimentary RSVP)

Sign-up Now!

About the book:

“Between Iran and Zion” offers the first history of this vibrant community over the course of the last century, from the 1905 Constitutional Revolution through the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Over this period, Iranian Jews grew from a peripheral community into a prominent one that has made clear impacts on daily life in Iran.

About the author:

Lior is an associate professor of history and Jewish Studies. He is a social historian of the modern Middle East with particular interests in the histories of the Jewish people and other minorities of the region. His first book, titled Between Iran and Zion: Jewish Histories of Twentieth-Century Iran (Stanford University Press, 2018) examines, against the backdrop of Iranian nationalism, Zionism, and constitutionalism, the development and integration of Jewish communities in Iran into the nation-building projects of the last century. He is currently working on two book projects: The Origins of Third Worldism in the Middle East and a new study of the Iranian-Jewish Diaspora in the U.S. and Israel. He teaches on the modern Middle East, Iran, Jewish histories of the region, and Israel-Palestine related classes.

For more about the book: “Between Iran and Zion: Jewish Histories of Twentieth-Century Iran.”

Sponsorship opportunities available:

info@americansephardi.org

===

The ASF Institute of Jewish Experience presents:

The Evolving Nature of Humanity in the writings of Hakham Eliyahu Benamozegh (1822-1900)

(3 Part Series)

Join us for the final part of the series “Insights from our hakhamim by students of The Habura”.

Thursday, 24 March at 12:00PM EST

(Ticket: $5 per session)

Sign-up Now!

About the speaker:

Ohad Fedida attended the Talmudic University of South Florida. He is now completing a B.S in Psychology from Florida International University and is a research assistant at the TIES Lab. He is working toward a Clinical Psychology, PhD. Ohad is also a student at TheHabura.com

Sponsorship opportunities available:

info@americansephardi.org